Greenwich Sound. A radio station ahead of its time?

By Cliff Osbourne. March 2025

If you lived in the London Borough of Greenwich in the early 1980s, and subscribed to Greenwich Cablevision, you may well have listened to Greenwich Sound at some point. It was one of the services available for subscribers, and was an early example of what would be termed a community radio station now. Today, in the UK, the term community radio refers to a system of licensing small and mainly very local not for profit radio stations. This began back in 2002 under the then regulator, the Radio Authority, with a pilot scheme known as ‘Access Radio’. This has since morphed into the large numbers of community stations that can be heard across the country today. Greenwich Sound was operating some 22 years before this and it wasn’t the first. (The picture to the left shows the Greenwich Cablevision HQ at 307 Plumstead Hight Street probably around 1971-72).

To begin, some background. The distribution of video and audio via cable can trace its origins back to the late 1920s. The idea became much more prevalent as Britain rebuilt its housing stock after the 2nd World War. The multi-occupancy blocks that sprang up in the 1950s and 1960s often had communal aerials or distribution systems for TV reception. However, it was in the early 1970s that cable really came into its own. Apart from Greenwich there were also systems in places such as Bristol, Sheffield, Swindon and Wellingborough in Northamptonshire. The cable system in Greenwich came into being because of the geography of part of the borough. Plumstead, Abbey Wood and parts of Belvedere, which was actually in the Borough of Bexley, were low lying and experienced poor TV reception. This was because Shooters Hill shielded them from the main transmitter at Crystal Palace. To try and get around this a group of local TV retailers had set-up Woolwich Relay. They had erected receiving aerials on a high point which could obtain good reception of Crystal Palace and distributed the signals via cable to subscribing homes. This is what became Greenwich Cablevision and by January 1972 it reached some 12,000 homes. Apart from the main channels, BBC1, BBC2 and London ITV, subscribers could also receive two out of area ITV services, Southern and Anglia. Greenwich also became the first system to start a local TV service following the granting of experimental licences in 1972. (The video on the left is a TV report from the time. The video below is a more recent look back at those times).

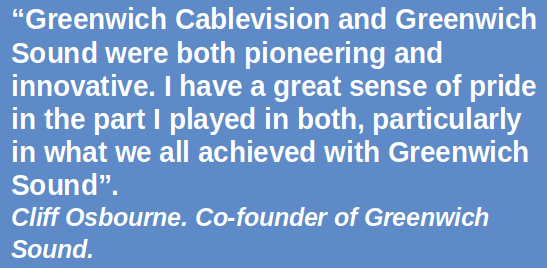

Enough of the history of cable television, though, and back to the Greenwich Sound. For its origins we really need to go back to the late 1960s. All of the ship-based ‘pirate’ stations had closed down (Radio Caroline of course returned in 1972 and remains on-air today) and this had led to the birth of a number of land-based unlicensed stations. Radio Jackie is probably the most famous of these. They broadcast for short periods, mainly on Sundays, to smaller areas and simply played music. These stations are a story all of their own, but relevant as the founders of Greenwich Sound all came from a background of land and ship-based pirate radio. There had been an earlier, entirely unofficial, ‘experiment’ in putting a radio station on the cable. Radio Cabletown appeared for a while in the mid-1970s on Friday nights. It just played music, but also accepted phone-in requests. There was also some thought given to using a very low powered VHF transmitter placed close to Cablevision’s receiving aerials to inject a radio station into the system, but after a couple of test broadcasts it proved to be not very practical. There things rested until the latter part of 1979 when Bob Lawrence, Terry Barnes and myself came together to make plans for what would become Greenwich Sound.

One of the problems with being a pioneer is that you don’t have the luxury of getting advice from somebody with experience in your chosen field. For us at Greenwich Sound we were almost in that position, but not quite. Radio Thamesmead, quite literally on our doorstep, was already operating on the Rediffusion cable system there. Radio Basildon and CRMK in Milton Keynes were also on the air and there was a station in Walworth, south London. We paid visits to both Radio Basildon and CRMK on a sort of fact-finding mission which helped to focus our thoughts and then sought a meeting with Maurice Townsend, the Managing Director of Greenwich Cablevision. Townsend listened carefully to our proposal to provide a local radio service to complement the existing local TV service, now being run by volunteers. He seemed a bit wary of us thinking we were a bunch of radio pirates, which to be fair we were! His concern seemed to be that we would turn a transmitter on, or as he put it “hang an amplifier out of the window”. However, to his lasting credit, he agreed that we could go ahead, but insisted that we became a properly constituted body rather than a group of individuals. So, we formed the Greenwich Cable Radio Society and, resisting the temptation to hang any amplifiers out of any windows, we got to work.

From the outset I think it fair to say that we were stepping a bit out of our comfort zone. We knew how to ‘do’ music radio, having by this time gained a fair amount of experience in it, but speech radio, or rather a mixed music/speech format, was a bit of a jump into the unknown. We had to be local. We knew that. It was the single biggest thing which would set us apart from any other radio station our audience could choose, or in today’s terminology, our USP. However, we knew enough to realise that our ‘localness’ had to be palatable, it had to be easily digested. As time went on we got the hang of it and developed a good balance between music and local content, some of which was pretty innovative, but that’s getting ahead of ourselves in the story.

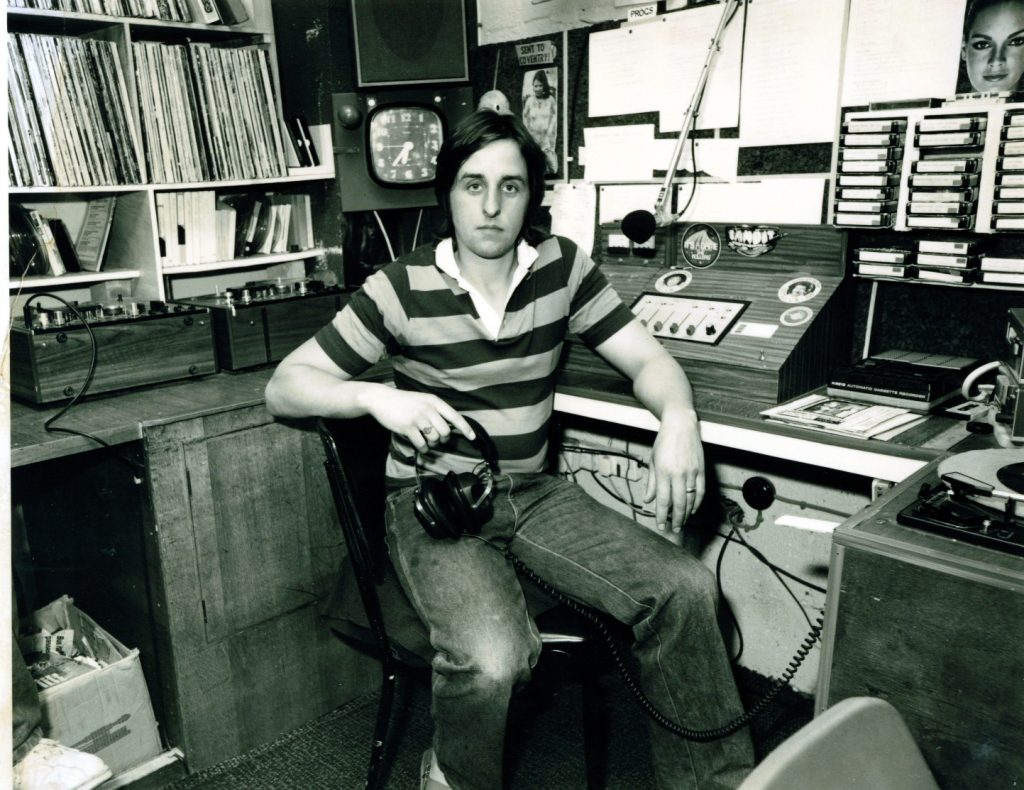

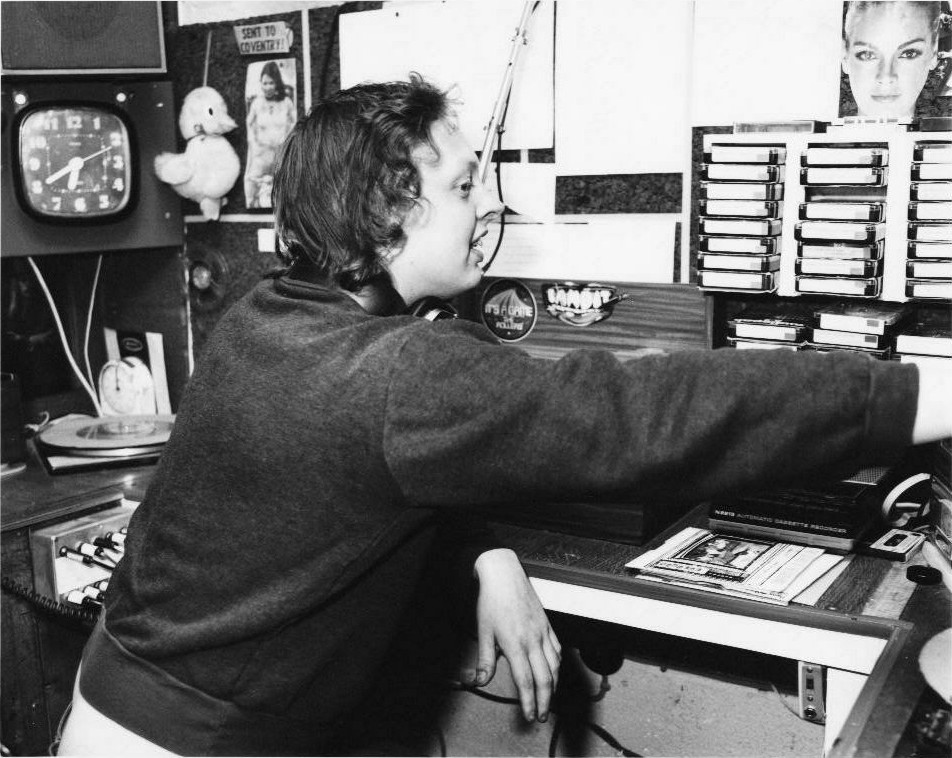

Rob Leighton, who we had worked with on land-based pirate London Music Radio, joined us as he had an engineering background. Rob, sadly now dead, brought much needed technical knowledge to the team and we set the date for the first broadcast by Greenwich Sound. This was to be Saturday, March 1st 1980, but the problem was that the only working studio available to us at the time was in my bedroom at home! The local TV studios were in two converted garages under a tower block on the Glyndon Estate, just off Griffin Road in Plumstead (the block sadly long since demolished). The next garage in line, which had been used for storage, was given to us to build a studio. It needed some work! We had to install a secure entrance door and divide the space to give us office and studio areas, but this was nowhere near ready for use on March 1st. So the first broadcast was recorded in my bedroom on an open reel tape recorder. We needed to be adjacent to the TV studio as it was an ingestion point on the system, that is to say one of a few points where we could access the cable for transmission purposes. Greenwich was an RF system and services were transmitted using the same or similar frequencies to over the air transmissions. Greenwich Sound programmes would be broadcast via the audio frequency of the local TV channel, so listeners would need their television on to be able to hear us. However, subscribers could also receive VHF(FM) signals via the cable through their hi-fi tuners. This meant Greenwich Sound could also broadcast in FM stereo and a frequency of 90.2MHz was allocated for the purpose. One happy consequence of this was that, being an RF system, there was some leakage of signal from the cable. If it passed your house and you had a radio tuned to 90.2MHz FM in close proximity you would hear our programmes whether you were a Cablevision subscriber or not. (The picture to the right shows Terry Barnes in our first studio).

So, launch day arrived and we gathered in our half-built studio, or ‘The Complex’ as it had become known. This was our little joke about the size of the accommodation. We plugged in the tape machine, laced up the tape and at 10am or 12 noon (sorry I can’t remember which) we pushed the play button and Greenwich Sound was on the air. The initial programme was three hours in length and the first record played was the latest single from Squeeze (local lads made good), ‘Another Nail in My Heart’. The first part of the show was a general segment of music and local information and this was followed with selected records from the Greenwich Sound Tip 20. This was a prediction chart containing stuff that wasn’t actually in the official charts, but that we thought ought to be. It was part of our aim to provide something different to that which could be heard elsewhere. As the tape rolled we wondered whether there was anyone listening. Subscribers to Greenwich Cablevision numbered around 6,500 at the time, and working on the basis of an average of four people per household there was a significant number of potential listeners. We gave out the phone number and to our delight it rang, and continued to do so. Greenwich Sound had arrived. (The pictures to the left and below show two more views of our first studio).

Over the following weeks we got on with building the studio. The walls were painted, carpets laid and a partition constructed to isolate the studio from the office area. We moved in various pieces of furniture and built a housing for the studio equipment. My ‘bedroom’ studio was dismantled and re-installed in its new home and the addition of various other pieces of equipment gave us a pretty comprehensive sent-up. This meant we could now run programming on both Saturdays and Sundays and the addition of a further piece of equipment enabled us to also launch the FM stereo service on 90.2MHz. However, on the down side, Rob Leighton decided to leave us over a difference of opinion on a particular technical matter and he was replaced by Jim Kelso. Jim was another veteran of the London land-based pirate scene and he took over the engineering role and, although not a broadcaster, he was heard from time to time on-air.

Now, we get to the point in the story where chronology is going to have to take a back seat. I have written this from memory, aided by those of Bob and Terry. None of us ….how shall I put this?….are now in the first flush of youth and we are dealing with events that, at the time of writing, took place some 45 years ago. From here on in I won’t be following a timeline as such, but dealing with various events and developments as Greenwich Sound grew.

Programming: Music, news (both local and national), sport, features and specialist shows were all elements of our programming that had to come together, complement each other, to form the complete package. Those who purported to know better would tell us everything needed to be segmented. For example, someone from the local pub games association could come in and spend 30 minutes reading the cribbage and shove halfpenny results. Following that we could perhaps play a couple of records, although nothing too ‘poppy’ and then it would be time for a talk about local history. This, we were told, was the way to give the community access to the radio station. To us this approach, a sort of audio version of random notices stuck on a board, would simply serve to make the station completely unlistenable. Rather than have a complete programme about local history for example, we’d create short features which would sit comfortably in between a couple of songs because they were creatively produced to do exactly that. Features played a large part in the sound of the station and all of our general programming was built around them. It enabled us to ensure that the information stayed relevant and palatable. Editing gave us the opportunity to make somebody who possibly wasn’t a great communicator concentrate on their specialist subject, safe in the knowledge that we would tidy it up and give it the best chance of being understood and enjoyed. (The picture to left shows Mark Lawrence in the first studio).

One big advantage we had was that all three of Greenwich Sound’s founders actually lived in the area, and in the case of Bob and I, grew up there. When we talked on air, we knew the patch sideways, backwards and upside down. When we gave traffic information, we could suggest alternative routes without thinking. We played records too, but our speech was spoken by local people who knew the patch and understood the local people, after all we WERE the local people. Almost all of those who would broadcast or contribute to the station were locals too. Once we had launched things began to move quickly and it wasn’t long before we were producing programming seven days a week albeit for short periods. All programming at this stage was of a music based magazine style. Weekday mornings were presented by Bob Lawrence and one memorable occasion Bob had his hair cut by a local hairdresser live on air. Weekends were covered by all three of us. Prior to going on air we had got hold of a large book which listed just about every organisation operating within the Borough of Greenwich. We contacted pretty much all of them asking to be placed on their mailing lists to receive any press release they might issue. We had also contacted Greenwich Council, local MPs and GLC members and anyone else we could think of. This led to large wodges of stuff arriving by almost every post which was used to put together our local news bulletins. (The picture to the right is me in the first studio).

Our team expanded when Mark Smith joined us. Mark was our first ‘proper’ journalist and he quickly became adept at condensing multi-page press releases into a couple of paragraphs which conveyed the nub of the story. Not only could he write the copy, he had an excellent voice for reading it too and gave the local news bulletins the same authority the IRN readers gave the national news. A special concessionary licence from Independent Radio News, costing just £1 a year, enabled us to carry their hourly bulletins of international and national news which we could access via LBC. Like many commercial radio stations we tagged our local news, initially just at the weekend, on to the end of the IRN bulletin. However, our approach differed from convention in that we deliberately kept the local bulletins short and to the point, choosing instead to concentrate on a weekly two hour ‘round up’ of the week’s local news items. Our reasoning was that this would give us the platform to devote more time to each story, taking the opportunity to get interviews or relevant reactions sorted. Sunday afternoon was, in our opinion, an ideal time for the audience to relax and properly listen to what had been happening in their borough during the previous seven days. The show was called Downtown and was wonderfully produced by Mark Lawrence, who was on the payroll of our MSC scheme described later. Apart from physically bolting the show together, Mark worked closely with the trainee journalists on the scheme, giving them the benefit of his extensive broadcasting knowledge and creative brain. As mentioned earlier, back then this way of dealing with local news parted from convention, and I would go so far as to say it was extremely innovative and even revolutionary. Bob Lawrence relates that he used this approach much later when applying for a local commercial radio licence in Staffordshire but the Radio Authority, the regulator at the time, couldn’t get their head around it and to this day Bob thinks it is one of the reasons his application was unsuccessful. Downtown, or elements of it, were to remain part of Greenwich Sound’s output until the very end. Alec Martin became Head of News and took over from Mark and later Chris Cardell and Andrew Waller were responsible for our news output. The show remained important to our ‘localness’ although over time as resources and staff permitted our local bulletins became longer and a little more in depth.

Sport had a big role to play too. We developed good relationships with local football clubs Charlton Athletic and Welling United, but covered many other sports as well. I remember regular reports from Crayford Speedway, for example. Our Sports Editor Simon Moffatt would later go on to work at Capital Radio and then went on to spend many years on the radio in Merseyside. He was assisted by Terry Morris who had many connections in the local sporting world. As mentioned earlier all our general programming was, what we hoped would be, an entertaining mix of music, features and local news and information, but we would, on occasions, include longer speech elements. For example, interviews with local MPs, council leaders and GLC councillors. We also carried good coverage of local elections when they were taking place, spending all night following ‘counts’ at Woolwich Town Hall so we could broadcast the results early in the morning. Alec Martin indulged in what we’d call investigative journalism today, putting together a special programme on the tragic fire in New Cross in 1981. Although a bit out of our area the ramifications of it were of huge relevance to the large Afro-Caribbean community in the borough. He also interviewed the controversial GLC leader Ken Livingstone early in his reign at County Hall. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_Cross_house_fire

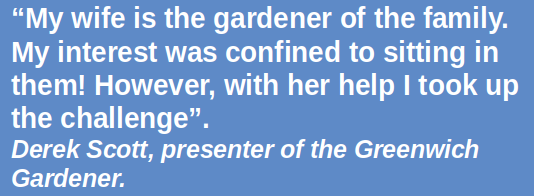

One of our regular early features was called ‘The Greenwich Gardener’ which, as the name suggests, consisted of gardening tips. This was hosted by Derek Scott, another recruit to the team. Derek shares his personal recollections. “Having grown tired of the office politics at my local hospital radio station, Radio St Nicks, I’d given up broadcasting around late 1977/8. Previously I had worked alongside Cliff Osbourne & Bob Lawrence at Radio St Nicks and on the slightly naughty Radio Cabletown mentioned earlier, plus a few blink and you’d have missed me programmes for London Music Radio. When Greenwich Sound started I contacted them to see if there was anything I could do to contribute to the station. I was told that I could contribute Theatre reviews which I did on a few occasions and also voice the weekly tips from the Greenwich Gardener. Now anyone who knows me would say that my interest in gardens was confined to sitting in them, getting a suntan or enjoying the fruits of others’ labours. Ignoring that I took up the challenge but always introduced it as “This is Derek Scott with this week’s tips from the Greenwich Gardener”. All these years later I can’t remember who produced the tips but somewhere along the way my wife, the real gardener of the family, took over the writing. Years later when I had joined Meridian Radio, a South London hospital radio station which had morphed into an internet community station, we decided to revive the Greenwich Gardener, this time written and presented by my wife Sally. We were amused to get a tweet noting the return of the Greenwich Gardener from Mark Smith whose role in Greenwich Sound is mentioned earlier”.

We had a number of more specialist programmes too. It seemed to us that much on the radio aimed at children and young people was at best well meaning but didn’t deal with what really interested them and at worst it was condescending. This wasn’t surprising as it was all controlled by adults and their view of what was good for ‘the kids’. We thought we’d turn the whole thing on its head. If we were to have a programme for young people then it ought to have a young person producing and presenting it. ‘Young Greenwich’ was to be aimed at the early to mid teens and Chris Cardell was selected to front it. Chris was I think 14 or 15 at the time and whilst he received training and guidance from us, what went into the programme was very much down to him. He was after all better placed than us to know what would appeal. ‘The Radio Picture Show’ was a programme about films and film music. It looked at classic movies, up-coming releases and films showing at local cinemas and was produced and presented by Tony Watts. Tony had been the programmer for Greenwich Cablevision’s early subscription film channel, ‘Screentown’. He was also responsible for introducing breakfast television on the local channel, pre-dating the BBC by a week! Tony’s knowledge of the film world was second to none and he always produced a show that was entertaining even if you weren’t that interested in the movies. His other contribution was a programme called ‘Jazz Sound’, which played a broad range of the genre. Some 10 years later London would get a designated jazz radio station!

We didn’t have a dedicated programme on local music as such, but the borough had a lively local music scene which we tried to reflect across the output. We often had local bands in to chat and play their music, particularly if they already had some recorded. I do recall some acoustic sessions too, and on one occasion attempting to record The Who when they played at Lewisham Odeon which didn’t quite work out. Gary Morgan was a loose coordinator for bringing in local bands and musicians, a role he also carried out for the local TV service. Aside from local music we did have a programme on new, or emergent, music. This was called ‘Creatures What You Never Knew About’ and was produced by Bob Pearce with Mark Smith presenting. Early material from bands such as The Smiths, Aztec Camera, Prefab Sprout and Scritti Politti was featured. We also introduced a Reggae show as the genre had a good following in the area. Initially it was presented by Bob Lawrence but was later badged ‘The Greenwich Sound System’ and taken over by ‘Papa’ Francis. He ran a reggae record shop on Plumstead railway bridge and so had access to the latest material. Other specialist shows included ‘Greenwich Country’ presented by Pete Larne, He came to us after long running country music shows on a couple of local hospital radio stations. There was also ‘The Funktion’ which carried soul and funk music and was presented by Andrew and Julie Morrison. People of Asian origin were also well represented in the borough. The local TV channel was already carrying some programming, so extending this on Greenwich Sound was a natural progression. Avtar Litt, who would later go on to found the UK’s first fully licenced Asian station Sunrise Radio, came on board to do a programme of mainly Asian music. This later developed into a programme called ‘Rang Mahal’, which also carried speech content. It was produced and presented by Manjit Virdi. There was also a short lived evening service under the banner ‘Oh What A Night’.

Sales & Commercials: As far as covering running costs was concerned we were pretty much on our own. Greenwich Cablevision provided our accommodation for free and also covered the electricity costs, but we received no grants or funding from local or central government. Fortunately the licence we operated under allowed us to take paid advertising. We had the expertise to produce the commercials but selling the airtime was something quite new to us so we needed a salesperson.

I can’t recall now whether we found him or he found us, but Sir Robin Philips BT joined the team as Head of Sales, which certainly looked impressive on our notepaper and business cards. Robin was a larger than life character with a very upper class accent who drove a Rolls Royce. He was pretty ‘posh’ compared to us but he had a sort of boyish enthusiasm for the project and he got to work. We did wonder how someone who spoke ‘proper’ might be received by the average Plumstead shop keeper or business owner but some of them obviously warmed to Robin as he did actually make sales. Early advertisers included the Lakeside Leisure Inn, KT Coachworks and Colin’s Super VG Store. A lady called Audrey Newman later took over selling our airtime, but ‘Sir’ Robin would feature again in our story.

We produced all our own commercials, a task initially undertaken by Bob Lawrence, but Mark Lawrence also did quite a bit. Over time what we earned from airtime sales made a contribution to covering our running costs. I recall that we colour coded the cartridges containing the commercials with a red dot. If you look at the colour photo of our second studio to the left you can count 13 of these, so we weren’t doing badly!

MSC Youth Opportunities Programme: The Manpower Services Commission (MSC) had been created back in 1973 by Ted Heath’s Conservative Government. It worked within the Department of Employment and by 1978 it was responsible for delivering the Youth Opportunities Scheme. This had been introduced in 1978 by James Callaghan’s Labour Government as a way of helping 16-18 year olds into employment. It was expanded under Margaret Thatcher in 1980 and ran until 1983 when it was replaced by the Youth Training Scheme.

Radio Thamesmead ran a scheme which seemed to provide as many benefits for them as the youngsters, so we decided to apply to run one as well. Under the scheme we would get funding to provide work experience for youngsters who were seeking work but unable to obtain any. The money would pay a co-ordinator, give the youngsters a weekly allowance and cover the scheme’s expenses. We were able to rent a shop on Plumstead Road near to the railway station in which to base the scheme. Unfortunately it wasn’t possible to move the studio there but it did give us a ‘presence’ on one of the main thoroughfares in the borough.

The young people placed on our scheme came from a variety of backgrounds and had varied abilities. Some were able to help with the radio station whilst others of a more practical bent were involved in an idea we had to help elderly people in the borough with decorating etc. About this time we also acquired a former London Transport RT Bus, or rather Robin Philips ‘rescued’ it from Biggin Hill Airfield. We found a place to store it and some of the trainees on the YOP scheme went to work helping to restore it. The bus would later go on to play a part in our campaign to be granted a licence to broadcast.

The other thing of note we did with the scheme was to launch a magazine, The Broadsheet. I remember Mark Lawrence being Editor)

The Campaign for an FM Licence: Without wishing to take anything away from our cable broadcasts, or indeed Greenwich Cablevision’s trust in us to provide a quality product for their system, it was being tied to the cable that placed the biggest restriction on us. In order to listen to Greenwich Sound you had to be in the same room as your connected TV or FM tuner. You couldn’t, for example, listen in the kitchen (unless you turned the volume up) or whilst driving around the area. It also presented difficulties when it came to trying to sell airtime. How do you sell something the potential advertiser possibly can’t sample? It was clear to us from an early stage that being able to broadcast conventionally on FM was a surer way to grow and provide a service for the whole of the borough.

Today the regulator OfCom regularly invites applications for community radio licenses. Had this been the case in the early 1980s it would have been easy to draft our application and very likely we would have been awarded a licence. Almost certainly we would have broadcast on-line and perhaps on DAB too, but back then there was no internet and no DAB and the IBA regulated all non-BBC radio (i.e. commercial radio) but had no remit to invite applications for community radio licenses. The UK has always over-regulated broadcasting, even in today’s so called ‘light touch’ era, and has been slow to allow innovation. We were up against a system that constantly said no spare frequencies were available for such things despite always finding some when it suited. There would be many hurdles to jump to even get a sniff of an outside chance of maybe, one day, getting a licence to broadcast! Undeterred, or perhaps we were just plain bonkers, we launched a campaign to be awarded one. John Cartwright (then MP for Woolwich East) raised the whole matter in Parliament in February 1981.(Hansard)

We wrote to anyone we could think of laying out our case and seeking support and were heartened to get very few negative responses. Most local organisations were in favour of a genuinely local radio station as was Greenwich Council and local GLC members. All of the local MPs were on board as well. We’d even gone to the extent of making an agreement with Radio Thamesmead that if only one frequency for the area was available we would share it. As the campaign progressed it seemed the attitudes in Whitehall were shifting to the extent that what we wanted might be possible. We were told Home Office officials were minded to consider allowing some sort of community radio experiment, but we would need to demonstrate there was a need for such a service. We already had many letters of support but we also launched a petition so we could demonstrate support from the general public in the borough, the very people who would hopefully listen. This ended up with 4,000 signatures.

We arranged to deliver our petition to 10 Downing Street, arriving on board the Greenwich Sound Bus. We nodded to the police officers at the door which was opened, not by the Prime Minister sadly, and our petition accepted. Next it was on to the Home Office for a meeting we had arranged with Lord Belstead who was the Minister responsible for broadcasting matters. The meeting was friendly but business like. He listened, made notes and asked a few questions. We left encouraged that we had made a good case and by the fact the meeting would probably never have happened unless wheels were really turning. Sadly it was to be a false dawn as the hoped for community radio experiment was shelved in the end and that was that. The trip did get coverage in the local press though, including the Kentish Independent. (See image to the right).